MC: I see you have worked on both games and films. What in your opinion is the difference in creating concepts for one or the other? Which do you prefer to design for, video games or films and for what reason?

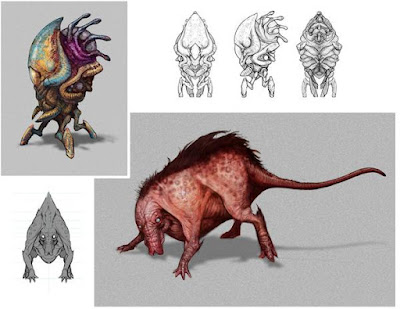

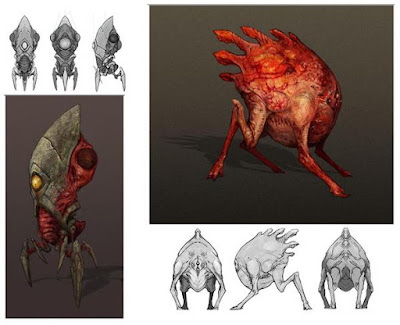

MC: I see you have worked on both games and films. What in your opinion is the difference in creating concepts for one or the other? Which do you prefer to design for, video games or films and for what reason? JSM: I’ve done a lot of work for both the film and game industries. There are quite a few differences, but the basics are the same. For film, the level of finish in the initial design phase is incredibly high. As I mentioned before, oftentimes in the first pass of a creature design, I have to take it as far as I possibly can so that the design looks like a still from the potential film. In video games you don’t do that. In video games you literally design from the silhouette out. You determine what the basic shape is of the creature and then start to flesh out the details. In film you’re doing both at the same time and it’s a bit more hectic. Also in film, the time in which you have to work is much shorter. You don’t often have time to go and explore. In video games, you will get that time. In film, you will end up using more 3D, more photo elements to convincingly execute the designs. In games you can pretty much just work traditionally in Photoshop without having to add any photo elements until the very end, if at all. The level of detail is very different in games and film. There are also different restrictions. If you’re working on a film and you’re designing a creature suit, you have to make sure that a performer can walk in this thing successfully. You have to keep in mind weight distribution, the weight of materials that are going to be used to create the suit. A lot of factors are involved. If it’s a visual effects character, that goes out the window.

In video games, you will get that time. In film, you will end up using more 3D, more photo elements to convincingly execute the designs. In games you can pretty much just work traditionally in Photoshop without having to add any photo elements until the very end, if at all. The level of detail is very different in games and film. There are also different restrictions. If you’re working on a film and you’re designing a creature suit, you have to make sure that a performer can walk in this thing successfully. You have to keep in mind weight distribution, the weight of materials that are going to be used to create the suit. A lot of factors are involved. If it’s a visual effects character, that goes out the window.

For video games, you might have to design around a specific poly count. They might not have a lot of polys to resolve your design so you might have to design very simply if it’s a low level bad guy. Sometimes in a game, you actually have to design creatures around the same animation rigs. It’s very common in video games for different characters to share animation rigs, and you have to design it accordingly so that the creature’s limbs don’t collide with the geometry and can actually share the same animation cycle.

For video games, you might have to design around a specific poly count. They might not have a lot of polys to resolve your design so you might have to design very simply if it’s a low level bad guy. Sometimes in a game, you actually have to design creatures around the same animation rigs. It’s very common in video games for different characters to share animation rigs, and you have to design it accordingly so that the creature’s limbs don’t collide with the geometry and can actually share the same animation cycle.

MC: Can you provide any tips on creating orthographic (turnaround) design sheets? What are the specifics (views and details) a CG modeler usually needs in order to turn the 2D design into a 3D design?

MC: Can you provide any tips on creating orthographic (turnaround) design sheets? What are the specifics (views and details) a CG modeler usually needs in order to turn the 2D design into a 3D design? JSM: Fortunately, nowadays I don’t really do that many orthographic views. I’ve rarely done an orthographic view for a film; that tends to be unnecessary. In video games I used to do them all the time and there are a few tricks. One I would use in particular was that after I designed the creature and did a full painting, the pose of that creature would usually be three quarters. I would find that creature’s center line, the very center of the design, select it, and select half of the creature and drag it onto a new document in Photoshop. Then I would warp and distort that three quarter view until it was a full front view. I would also flip that so I could get the full front view of the creature. Now, the front view and the back view are identical in silhouette. So once I finished doing the front view, it was very easy to do the back view. Then finally I would do a profile and that’s simply just a matter of drawing guidelines from all the key landmarks and connecting the dots in profile. It’s a very boring process and I’m glad I don’t do it that often anymore.

MC: Out of every project and every creature you have worked on and produced, what do you feel is the most successful concept you have come up with? What is it about that design that you feel makes it the most memorable?

MC: Out of every project and every creature you have worked on and produced, what do you feel is the most successful concept you have come up with? What is it about that design that you feel makes it the most memorable? JSM: Of all the projects so far, I think my all time favorite was “Clash of the Titans”, specifically the Kraken design. There is something incredibly powerful about that creature and I was pretty happy about the way it was executed. With that particular design, I went from loose sketches to finalized renders in Zbrush and Photoshop, and it took a very long time to design. So when it finally made it on screen, it was awesome to see the fruits of my labors come out so well. What I like about the design I think the most is how incredibly powerful the character is. It is unstoppable. It’s gigantic. It’s really just over the top, and the kid in me has always wanted to design something that massive and that powerful. To have that opportunity was just amazing. I was also just thrilled at how well it was executed. (Check for Clash of the Titan's concept art in Part 01 here) I was on a lot of creatures for that film—I designed Medusa, I did several passes on Calibus, I designed the witches, but the Kraken was the climax of the film. It was a big deal and it took a very long time to get right. It was just a very exciting process.

MC: Is there any genre, subject matter or field of work you haven't yet had the opportunity to work on that you would love to be involved in? IE; horror, sci-fi, film, games, whimsical, animated..

MC: Is there any genre, subject matter or field of work you haven't yet had the opportunity to work on that you would love to be involved in? IE; horror, sci-fi, film, games, whimsical, animated.. JSM: I’ve always been interested in working on an animated film. I’ve been looking at a lot of animated movies lately and have been floored by them. The production design, the attention to detail… I’d love to try that out. Currently I’m writing an animated series and I’ve had the opportunity to design my own characters for a show that I’ll be pitching this year, so that’s exciting. An animated film would be very appealing because it’s actually the opposite of what I do. Having to simplify forms and get characters to read with as few lines as possible would be a fun challenge.

MC: How does the use of 3D programs like Zbrush work to benefit a concept artist? Do you feel it is an essential tool to learn if you want to speed up the process or learn to draw your design from multiple angles? What are the advantages of a program like that to you?

MC: How does the use of 3D programs like Zbrush work to benefit a concept artist? Do you feel it is an essential tool to learn if you want to speed up the process or learn to draw your design from multiple angles? What are the advantages of a program like that to you? JSM: Learning a 3D program is essential. I work mainly with Zbrush. Zbrush has a lot of benefits. One of the biggest things I find that students struggle with isn’t necessarily the design of the creature, but how to execute it: how to draw it in perspective and how to light that creature. With Zbrush that isn’t an issue. You simply sculpt it and you get the lighting and perspective for free. The program has a ton of advantages. You can render out your character in different materials, light the creature and you can also show orthographic views of your design instantly. It’s a lot harder to do that from the ground up going into Photoshop, designing the character in grayscale, painting over it, and adding photo elements, while making sure that your lighting and perspective all work. Learning 3D is essential to the survival of concept artists today. I’m often surprised, when I’ve had the opportunity to work with other concept artists, to see how many of them are actually using 3D. Even concept artists whose work seems very painterly will actually rough out a composition in a program like Maya or Moto and paint directly on top of it. Even for environment artists, just using a simple program like Google Sketchup can make the process go much more quickly. As a matter of fact, if you were to use a combination of Google Sketchup and a lighting program called V Ray, you could finish sixty percent of your design in the computer. So again, very very important to learn 3D.

It’s a lot harder to do that from the ground up going into Photoshop, designing the character in grayscale, painting over it, and adding photo elements, while making sure that your lighting and perspective all work. Learning 3D is essential to the survival of concept artists today. I’m often surprised, when I’ve had the opportunity to work with other concept artists, to see how many of them are actually using 3D. Even concept artists whose work seems very painterly will actually rough out a composition in a program like Maya or Moto and paint directly on top of it. Even for environment artists, just using a simple program like Google Sketchup can make the process go much more quickly. As a matter of fact, if you were to use a combination of Google Sketchup and a lighting program called V Ray, you could finish sixty percent of your design in the computer. So again, very very important to learn 3D.

MC: What do you feel really helped to kick start your career and what allowed you to focus completely on designing creatures/characters? Do you ever get asked to produce other types of assets? IE; environments, weapons, vehicles..

MC: What do you feel really helped to kick start your career and what allowed you to focus completely on designing creatures/characters? Do you ever get asked to produce other types of assets? IE; environments, weapons, vehicles..

JSM: What really jumpstarted my career was working in effects houses when I was a kid. I lucked out. I got an internship at a low budget effects house thanks to my sculpting teacher when I was just thirteen, a man by the name of Jordu Schell. He’s most likely the industry’s best maquette sculptor and definitely one of the best sculptors in general. While interning at these special effects houses, I tried everything. I did everything from sculpting to mold making, and realized throughout the process that I didn’t really care much for making molds. I enjoyed sculpting, but noticed that a lot of sculptors out there didn’t necessarily design. Through the process of trying everything, I discovered that I really only cared about designing and was able to just focus on that. Once I had figured that out, my path became much clearer.

I hit the books pretty hard looking for inspiration, looking at other creature artists and studying their techniques. Mainly the illustrative designers like Miles Teves and Crash McCreery. I looked at a lot of comic book artists. I often do more than creature design. There are very few people out there who survive only as a creature designer, and as a concept designer, I’ve discovered that the more you can do, the longer you can stay on a show and the more secure your position can be. Not only do I do creature design, though that is my specialty, I also do character design, I do costume design, I do a little bit of environments and scenes, I do props, and I do vehicles as well. Being able to do everything is really important. Not to say that having a specialty isn’t, but being able to do everything just helps you survive and that’s really important as a concept artist. You will not always get the most ideal job. There have been times where I’ve had to just take on work that was really boring when the film industry slows down.

I hit the books pretty hard looking for inspiration, looking at other creature artists and studying their techniques. Mainly the illustrative designers like Miles Teves and Crash McCreery. I looked at a lot of comic book artists. I often do more than creature design. There are very few people out there who survive only as a creature designer, and as a concept designer, I’ve discovered that the more you can do, the longer you can stay on a show and the more secure your position can be. Not only do I do creature design, though that is my specialty, I also do character design, I do costume design, I do a little bit of environments and scenes, I do props, and I do vehicles as well. Being able to do everything is really important. Not to say that having a specialty isn’t, but being able to do everything just helps you survive and that’s really important as a concept artist. You will not always get the most ideal job. There have been times where I’ve had to just take on work that was really boring when the film industry slows down.

MC: What advice can you offer as a last bit of experience when it comes to building a strong portfolio? What do you think would help one artist get noticed over another; what should they include in their portfolio if they want to pursue a career in creature design?

MC: What advice can you offer as a last bit of experience when it comes to building a strong portfolio? What do you think would help one artist get noticed over another; what should they include in their portfolio if they want to pursue a career in creature design?

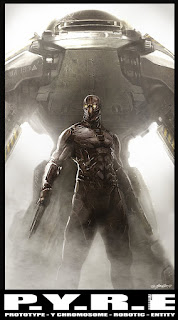

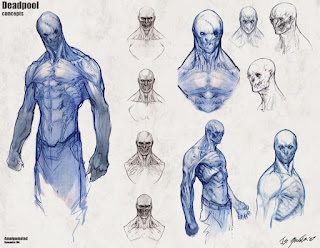

JSM: When I got out of Art Center, I started working immediately at Stan Winston’s. It was an amazing experience and it was incredibly validating. I believe what got me the job was the fact that I had a portfolio filled with original design work. No academic work, no still lives, no figure drawings, just one design after the other of aliens, werewolves, cyborgs, mechs, just anything that I could do to show range.

A bit of advice that I would give students who want to be creature designers in this industry, is to just focus on an original portfolio for as long as they can while they’re in school. Try to do a creature a week. Cover your bases. Do an alien. A werewolf. Almost every genre of creature that you can come up against. Don’t neglect fantasy, science fiction, horror— all of your bases should be covered. There is no maximum of images in a portfolio. The more the merrier. Of course you want to have the strongest images in your book, but quantity as well as quality will tell a potential client quite a bit about you. Show range. Show range of abilities, not just the same execution every time on every image. Show that you have designs that are accomplished in 3D, show drawings, show paintings, show photo manipulated pieces, show your clients what you can offer them. A portfolio is a very powerful tool. When I’m showing a potential client my book, I’m looking at the client’s reaction to the work. If they gloss over my drawings quickly, that means they don’t read drawings very well. If they’re focusing on the 3D work, then that’s how I will produce work for them. Whatever they are responding to. A portfolio acts as a menu to a client and you have to watch them go through your work to determine how best to design for them. Keep academic assignments out of your portfolio. I’ve noticed a lot of portfolios are filled with descriptions, and they’re really formatted, there’s a lot of text in there describing the artist’s process… the truth is if the images don’t catch the client’s attention, the words won’t. No one reviewing a portfolio ever reads your notes. It doesn’t matter what you write, it really is just about the images.

A bit of advice that I would give students who want to be creature designers in this industry, is to just focus on an original portfolio for as long as they can while they’re in school. Try to do a creature a week. Cover your bases. Do an alien. A werewolf. Almost every genre of creature that you can come up against. Don’t neglect fantasy, science fiction, horror— all of your bases should be covered. There is no maximum of images in a portfolio. The more the merrier. Of course you want to have the strongest images in your book, but quantity as well as quality will tell a potential client quite a bit about you. Show range. Show range of abilities, not just the same execution every time on every image. Show that you have designs that are accomplished in 3D, show drawings, show paintings, show photo manipulated pieces, show your clients what you can offer them. A portfolio is a very powerful tool. When I’m showing a potential client my book, I’m looking at the client’s reaction to the work. If they gloss over my drawings quickly, that means they don’t read drawings very well. If they’re focusing on the 3D work, then that’s how I will produce work for them. Whatever they are responding to. A portfolio acts as a menu to a client and you have to watch them go through your work to determine how best to design for them. Keep academic assignments out of your portfolio. I’ve noticed a lot of portfolios are filled with descriptions, and they’re really formatted, there’s a lot of text in there describing the artist’s process… the truth is if the images don’t catch the client’s attention, the words won’t. No one reviewing a portfolio ever reads your notes. It doesn’t matter what you write, it really is just about the images.

As for other pieces of advice, while in school students will learn quite a bit of theory, and this is good. This is all necessary. Color theory, shape theory, rules when it comes to producing convincing creature designs or design in general. The harsh truth that all students will come to realize is that as soon as they’re designing for the real world, for real clients, theory doesn’t mean much. In film, the people who are signing off on designs don’t know about shape theory. They don’t know about what it is exactly that academically makes a design good; they simply know what they like. I have found that once I understand what the client likes, I can get designs through. It is a harsh truth, but it’s very true. By the time you get into the real world, you will no longer be designing for your teachers; you’re going to be designing for your clients. So don’t butt your head up against a wall. Don’t fight your clients. Help them develop their ideas and be as accommodating as possible. Maybe later on when you’re accomplished enough, your opinion or your work will be sought after and you’ll be more trusted, but when you start working make sure you make your clients happy. You’ll last a lot longer.

As for other pieces of advice, while in school students will learn quite a bit of theory, and this is good. This is all necessary. Color theory, shape theory, rules when it comes to producing convincing creature designs or design in general. The harsh truth that all students will come to realize is that as soon as they’re designing for the real world, for real clients, theory doesn’t mean much. In film, the people who are signing off on designs don’t know about shape theory. They don’t know about what it is exactly that academically makes a design good; they simply know what they like. I have found that once I understand what the client likes, I can get designs through. It is a harsh truth, but it’s very true. By the time you get into the real world, you will no longer be designing for your teachers; you’re going to be designing for your clients. So don’t butt your head up against a wall. Don’t fight your clients. Help them develop their ideas and be as accommodating as possible. Maybe later on when you’re accomplished enough, your opinion or your work will be sought after and you’ll be more trusted, but when you start working make sure you make your clients happy. You’ll last a lot longer. MC: Jerad, I want to Thank you for all your time and the advice you have to offer regarding the in depth answers. I hope to continue to see your work in the film industry and your magnificent creatures grace the big screen. Good luck with the continued success of your career. To everyone reading, you can check out more of Jerad's work and continue to follow his updates on his blog: The Art of Jerad S. Marantz

MC: Jerad, I want to Thank you for all your time and the advice you have to offer regarding the in depth answers. I hope to continue to see your work in the film industry and your magnificent creatures grace the big screen. Good luck with the continued success of your career. To everyone reading, you can check out more of Jerad's work and continue to follow his updates on his blog: The Art of Jerad S. Marantz

Guest blogger Mike Corriero is a character, creature, and conceptual designer and illustrator living in New Jersey. Since graduating from Pratt Institute in 2003, Mike's client list has included Breakaway Games, Fantasy Flight Games, Allied Studios, Kingsisle Entertainment, Radical entertainment/ Vivendi Universal Games, Liquid Development, Zynga Inc, Challenge Games, Paizo Publishing and Hasbro Inc, among others. Mike's book "PLANET to PLANET creatures and strange worlds" includes hundreds of his sketches of creatures, robots, alien life forms and their environments. I recommend it for students focusing on visual development for games, or anyone who loves creature design. - J. G. O.

0 Yorumlar